Forecasting famine during a food glut

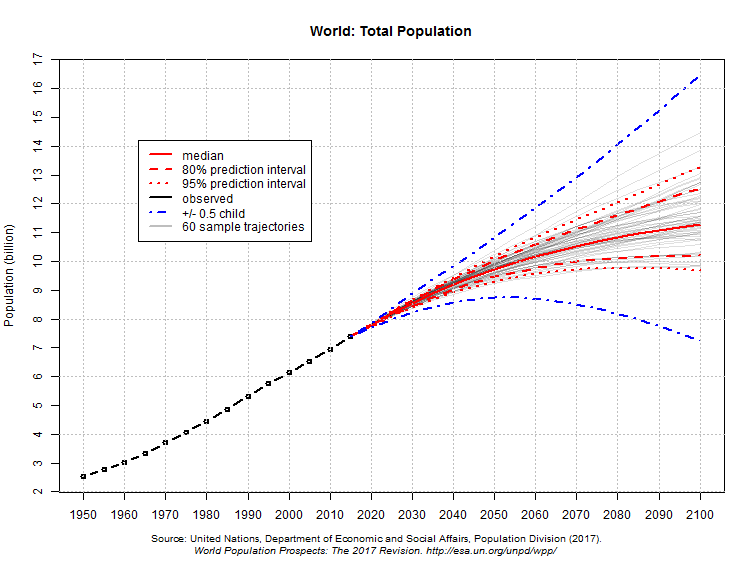

Reuters just released a special story about the historic levels of food stocks, and the associated drop in agricultural profits, both at the farm and the farm services level. This is interesting to me because almost all of the papers I have written and the research I have done has been motivated by the need to produce more food to feed the growing population. Many influential papers in agriculture have highlighted the coming food shortages, the need to double food production by 2050, etc. Almost every presentation, every correspondence, every poster in agricultural science at least mentions the coming challenges.

So were we wrong?

Land-sparing vs. Land-sharing

There has long been a debate in Ag science if we should focus on harvesting more food, fuel, and fiber from lands currently under cultivation so that less land needs to be cultivated (land-sparing), or if we should make our practices less impactful, even if that means more land needs to be cultivated (land-sharing).

The debate has not been resolved in academia, but Monsanto/Syngenta/Pioneer-DuPont aren’t waiting around. The story makes it clear they are pushing the limits of growing season length, which enables the successful cultivation of maize in short-season environments. We might soon be farming maize inside the Arctic Circle.

So, crisis averted, right?

The issues with land-sharing

Despite our best efforts, some impacts of cultivating the land seem unavoidable. Concerns such as:

- Loss of soil organic carbon

- Loss of biodiversity

- Reduced functional diversity

- Altered hydrology

- etc.

have all been observed when natural areas are brought into cultivation. But as highly intensified systems approach their limit, we might not have a choice. The theory has been that food shortages will drive up prices, which in turn will incentivize the expansion of land under cultivation. The expansion of maize towards the Arctic Circle follows the expected path. Almost…

The unexpected (at least to me)

What surprised me was that hold-over policy and technological improvements have driven farm-profits down even as land expansion is continuing. Research is a slow moving ship, and efforts started during food shortages are coming to fruition only recently. Agronomists generally believe in the wisdom of the crowd - each farmer is acting rationally, and therefore the system largely follows a rational path.

But now I am reconsidering - how can the system collectively move counter to the interest of most of the actors involved?